Musical scores

Four types of sources were used to produce this Critical Edition: published scores of Mohapeloa’s music, manuscript scores, other written documentation, and recordings. The first source is by far the largest and most important. Very few original manuscripts have survived, although more may surface through further research. (See African Choral Music: History.) Of the 135 extant scores published during Mohapeloa’s lifetime (1908-1982), 105 were published in Morija (Lesotho) in collections that are still on sale there, and 25 were published in Cape Town in a book that is now out of print. The list of extant published sources is as follows: (‘comprising’ means all the songs in a book are by Mohapeloa; ‘in’ means the collection included other composers)

32 songs comprising Meloli le Lithallere tsa Afrika I [African Songs and Extemporary Harmonizations book 1]. Morija, Lesotho: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. 1st ed. 1935; 1st reprint 1953; 2nd reprint 1977; 3rd reprint 1983; 4th reprint 1988.

32 songs comprising Meloli le Lithallere tsa Afrika II: Buka ea Bobeli [book 2]. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. 1st ed. 1939; 2nd ed. 1945; 1st reprint 1955; 2nd reprint 1980; 3rd reprint 1996.

28 songs comprising Meloli le Lithallere tsa Afrika III: Buka ea Boraro [book 3]. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. 1st ed. 1947; 1st reprint 1966; 2nd reprint 1977; 3rd reprint 1983; 4th reprint 1988.

5 songs comprising Khalima-Nosi tsa ’Mino Oa Kajeno [Shining Examples of Today’s Music]: Harnessing Salient Features of Modern African Music. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. 1st ed. 1951; 1st reprint 2002.

25 songs comprising Meluluetsa ea Ntšetso-pele le Bosechaba Lesotho. [Anthems) of Development for the Lesotho Nation]. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. 1st ed. 1976; out of print.

8 songs in Hosanna [Hosannah], 1st edition 1955.

2 songs in Binang ka Thabo [Songs of Joy], 1st edition 1963. Mazenod [Maseru]: Mazenod Institute.

‘Eben-Ezer’, individually published by Morija Sesuto Book Depot [n.d.]

‘Likhomo Mokoena’, individually published in the L.E.C. church newspaper, Leselinyana la Lesotho (Little Light of Lesotho], 9 March 1960.

‘Sefika sa Teboho’, individually published by [?] [n.d. 1966]

First editions and manuscripts

Some 1st editions of the Morija collections are housed in the Morija Museum and Archives (Lesotho). Copies of Meluluetsa are held in some libraries, including the Library of the University of South Africa. Original manuscript sources in the composer’s hand have largely disappeared, with the following exceptions some of which are late works, unpublished at the time of the composer’s death:

Some 1st editions of the Morija collections are housed in the Morija Museum and Archives (Lesotho). Copies of Meluluetsa are held in some libraries, including the Library of the University of South Africa. Original manuscript sources in the composer’s hand have largely disappeared, with the following exceptions some of which are late works, unpublished at the time of the composer’s death:

‘Chaba se kopane!’, ‘Ho tho’le tsoe NTTC’, ‘Phokolang fela se matla’, Pesaleme – Eric Lekhanya private collection, Maseru. Pesaleme is a sheaf of 38 arrangements by Mohapeloa of Dutch Mission Church psalm tunes with Sesotho texts, which Dr. Lekhanya found in his office at the Lesotho teachers Training College in Maseru – where Mohapeloa was working when he died.

‘Freedom in Unity – O.A.U. Anthem’, ‘Lesotho lefa la rōna’, ‘Sehopotso’, ‘Shoeshoe tsa Moshoeshoe’, ‘Thaba Bosiu [ii]’, ‘Tholoana lerato’, and most of the mss of the songs in from Meluluetsa – Ntsiuoa Joyce Mohapeloa Private Collection, Bloemfontein

‘Tlholohelo ea Ntlo ea Molimo’ – Morija Museum & Archives, File ‘JP Mohapeloa’

‘Lesotho, Tsiketsi sa Tlotla ea Afrika’ and ‘Thapelo’ (Haydn arr. Mohapeloa) – Southern African Music Rights Organisation (SAMRO) Archive (Johannesburg), Catalogue number AO2950

Mohapeloa sent manuscripts of all 32 songs in Meloli Book I to Yvonne Huskisson at SABC Radio Bantu (Johannesburg) in 1965. These are currently in the Richard Cock private collection, Johannesburg, and the letter that refers to them is in the file ‘Mohapeloa, J.P.’ in the Huskisson Collection, SAMRO Archive.

The 1965 ms is so close to the 1935 1st edition that one must regard it as the original ms, with a few very minor rethinks added in 1965 by Mohapeloa (mainly tempi), and it forms the basis for Volume I of this Critical Edition. Mohapeloa made many small revisions in the 1953 ‘reprint’ of this Volume that was then republished in subsequent editions, so much so that in reverting to the earlier version in this Critical Edition choirs used to singing the later version will be in for a surprise!

SAMRO has a few songs from larger collections that were published individually and other fragments or title pages. SAMRO has also re-published two Mohapeloa songs from Meloli in its dual solfa-staff notation series South Africa Sings:‘U Ea Kae?’ (1998) and ‘Nonyana Se-nya-mafi’ (2008).

Reliability of published scores as sources

Morija scores published by MSBD were printed at the Morija Printing Works (sometimes erroneously called ‘Morija Press’) and it is likely that the composer proof-read all of them, certainly from Meloli book 3 onwards, because he joined the Press as a proof reader in 1945. They are beautifully, and clearly produced. (See ‘Extract from Meloli book 1: First page of U ea kae?’.)

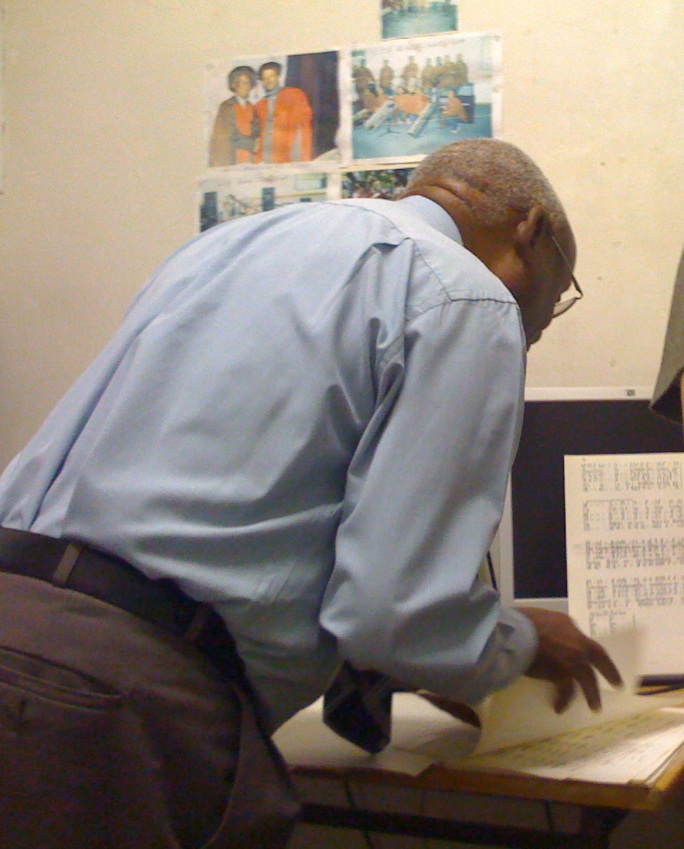

There are nonetheless typos here and there, which were not corrected in subsequent printings of Meloli and Khalima-Nosi. Published works constitute the majority of the sources used in this Critical Edition. Most of the songs from Meluluetsa exist in both published and manuscript versions, too, which is useful for verification of details. Manuscripts dating from Mohapeloa’s later life are in large print format: 4 plain A4 sheets gummed together and music written with a thick felt-tipped pen. Mrs Ntsiuoa Mohapeloa’s view is that this is attributable to the composer’s failing eyesight, but another suggestion is that this format was useful for classroom singing (J.S.M. Khumalo, pers. comm. 2.9.08). Mohapeloa’s script, both in his music notation and his song texts, is distinguished by its neatness and legibility.

Other musical sources

Jonathan Edwards transcribed 57 songs from Meloli into staff notation and printed them in Swaziland in October 1979). His Staff Notation Version of Choral Compositions of Mohapeloa (Waterford-Kamhlaba School, Box 52, Mbabane, Swaziland) contains the whole of Meloli 1 and the first 25 songs of Meloli 2, without translations. A copy of this collection is housed in the International Library of African Music (ILAM), Grahamstown and was consulted for this Critical Edition although it contains a number of mistakes, and I did not always agree with Edwards’ time signatures, grouping of notes, or voice registers. Other transcriptions exist, some of which have been reproduced by competition organizers. An example is ‘Mokhotlong’ transcribed by Ludumo Magangane and typeset by Carl van Wyk in 1997 for the Roodepoort International Eisteddfod.

Over decades of practice where choral songs have been performed by so many different kinds of choirs for varied functions, many hand-written, roneoed, gestetnered or electronic copies of individual songs have been made. (Some of them are still in circulation.) A common practice before the 1970s was writing songs out by hand from a borrowed score (itself often a copy), and thus versions exist in several different handwritings. Only in the 1990s did the practice of producing a standard collection of printed prescribed music for national choral competitions emerge, and there is still often no indication of the printed source of the songs reproduced there. For the purposes of this edition, therefore, these ‘circulating copies’ have not been used. They shed some light on the reception history of Mohapeloa’s music but not much light on its sources. What is interesting about most of them, however, is that they are rarely reproductions of the original Morija or OUP scores, and where they are copies of hand-written versions, they are usually not in Mohapeloa’s handwriting.

Literary sources

Other sources include Mohapeloa’s Prefaces to MLA I, Khalima-Nosi, and Meluluetsa, which are useful sources of information about his intention and in some cases sources of inspiration. His two autobiographical sketches — one in Sesotho and a shorter one in English — made for Yvonne Huskisson in the mid 1960s are also helpful, as is the biographical essay by his brother, Makibinyane Mohapeloa. Prefaces and forewords written by other people are also occasionally illuminating, for example Akim Sello’s foreword to Meloli I, and Chief Lebua Jonathan’s foreword and Diparata Gosh’s introduction to Meluluetsa. (See Mohapeloa: Sources of Information on Mohapeloa.)