Lyrics

Mohapeloa wrote his own lyrics (texts), occasionally adapting them from sources such as folksongs, hymns, the Bible, or music by other composers. Aside from Coronation March and Freedom in Unity the lyrics are in his home language, Sesotho. They are beautiful poems in their own right, although by and large he did not leave us with examples of the texts written out separately. They can be seen as poems once they are extracted from the scores in which they are embedded. (See African Choral Music: Languages. An exception is the 1976 O.U.P. collection, Meluluetsa ea Ntšetso-pele le Bosechaba Lesotho where texts are published separately as well as on the (tonic solfa) score.

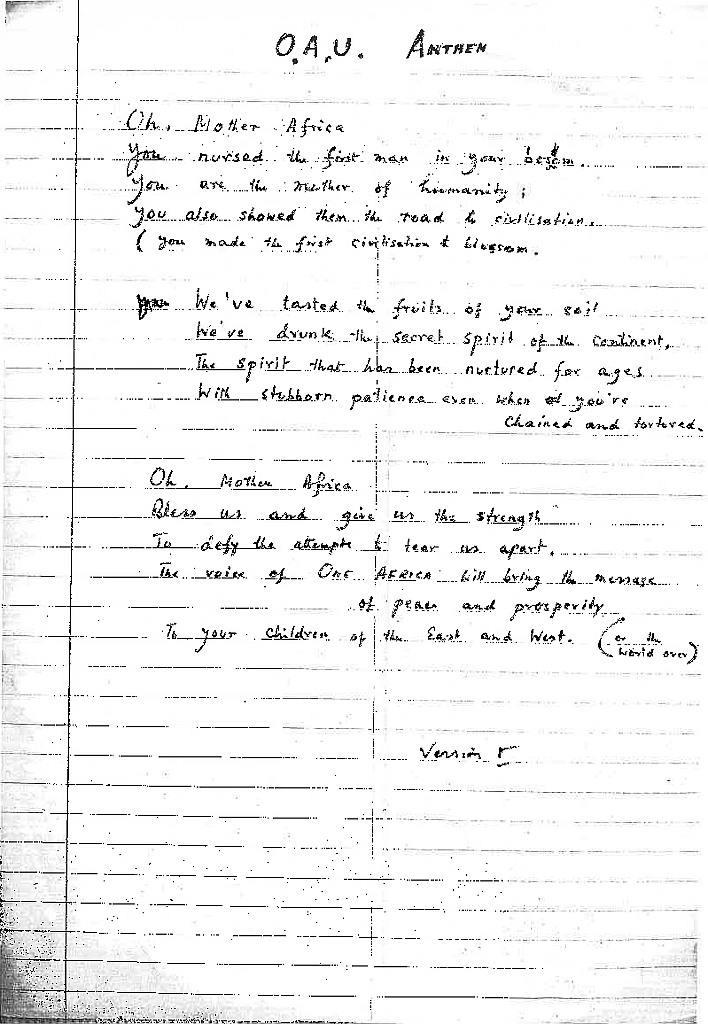

Evidence from two surviving handwritten drafts of other songs suggests that Mohapeloa worked on texts separately from the music – sometimes before, sometimes after, sometimes while composing the music. Freedom in Unity is an unpublished manuscript intended as an anthem for the (then) Organisation of African Unity. It is a rare example that shows how his lyrics evolved. Two drafts of the lyrics of this song, labelled ‘Version I” and ‘Version II’ on the manuscript are shown below, together with the text that he finally settled on.

Freedom in Unity final text

In most cases, the lyrics had to be extracted from the tonic solfa scores, where the words are interwoven with music notation, where different lines of text are sometimes allocated to different voice parts or lines are incomplete, and where several voice parts often share the same text. Added to this is the problem of repetition: it is sometimes unclear whether word or line repetition occurs for poetic reasons, to underscore a feeling or idea, or musical ones, to fit in with the musical momentum or vocal texture at a particular point. It is obvious where repetition is used, as a refrain (chorus). Most repetitions have been minimised in the texts presented and translated here, or are indicated by an ellipsis (…).

Translation

The lyrics are presented as poems on the inside front cover of each song, along with a phoneme-by-phoneme interlinear translation that shows what words literally mean and a poetic translation to help choirs or scholars understand a song’s meaning. Mohapeloa used upper case (capital letters) periodically, so we can see where new ‘lines’ of verse begin. In this critical edition long lines are occasionally run on for lack of space and repeated choruses/refrains are shortened.

Most of the literal translations were made by Dr Mantoa Motinyane-Smouse. A few translations by Mohapeloa himself exist, although sometimes these are ‘summaries’ rather than line by line translations. The South African poet Stephen Gray added suggestions for rendering the poetic translations more idiomatic in English, and the translations were edited by Mrs Mpho Ndebele in a way that often brings out deeper meanings and renders the poetic meanings embedded in the Sesotho more lyrically in English. The translations are not intended to be sung to the music. Choirs who need help with pronunciation of the Sesotho can download the Pronunciation Guide.

For the most part, Mohapeloa used the Lesotho Sesotho orthography, despite (more likely because of) changes made to this orthography by South African linguists in 1966. (See African Choral Music: Languages.) The question of orthography was a deeply political issue in the 1960s when these changes happened, and when the former Basutoland Protectorate was gearing up for becoming the independent Kingdom of Lesotho in 1966. There are still ‘two orthographies’: one used by Sesotho speakers in Lesotho, the other used by Sesotho speakers in South Africa.

The work of codifying and writing down Sesotho was started by French and French-Swiss missionaries in the 1830s when they first arrived in Lesotho. It was a language that until that time had not been written down. Several ‘French’ features of orthography survive in Lesotho Sesotho, including spelling the syllable pronounced ‘oa’ (‘wa’ in South African orthogrphy) or ‘ua’ (‘wa’) and ‘ea’ (‘ya’). The French encountered sounds that they wrote as diphthongs, and they used a number of hyphenations and accents, including é, ê, è, ō, and š. The ‘d’ sound when it came before an ‘i’ or ‘u’ sounded to the French somewhere between ‘d’ and ‘l’. They wrote it as ‘l’ but it is pronounced ‘d’ and in South African Sesotho orthography it is written ‘d’. Mohapeloa often elided words, perhaps to make them fit the musical sounds he wanted. There are many other issues and problems associated with translating Mohapeloa’s texts into English, partly due to his own personal usage of the language and partly to the fact that Sesotho is a rch and metaphorical language very different in construction and inflection from English.