Surendran Reddy

i was born in a hospital in durban, south africa at lunchtime on the 9th of march 1962. time, as douglas adams points out in the hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy is an illusion, lunchtime doubly so. when such a distinguished writer says something like this how can i be sure that i exist at all? hang on a moment while i pinch myself … (‘the life and opinions of surendran reddy, gentleman?’)

Surendran Reddy was a larger-than-life musician and personality, whose more than 100 compositions represent an extraordinary period in South Africa’s history – before, during, and after the end of apartheid.

In this biographical overview, we are unable to give him the benefit of the doubt of his own existence, but we do often give him a chance to have his say. For he not only composed prolifically, he also left us many beautiful and often quirky writings in which he reflects upon his struggles, his life, and his times.

Surendran Reddy immigrated to Bulawayo, Zimbabwe with his parents Dr. Y.G. Reddy and Mrs. Leela Reddy a month after his birth in Durban, South Africa in March 1962.

Piano studies

He began learning the piano at the age of five with Isabel Rademeyer, “a dear sweet lady, as gentle as a lamb, who taught with an almost maternal love and care”:

i will never forget how she sat quietly weeping next to me while i played the sublime tones of a mozart slow movement at the age of maybe 8 or 9. this ability to emote so intensively and her lack of inhibitions to expose her feelings consolidated for me what i already guessed to be the unbelievable expressive power intrinsic in all great music (‘preface’ to ‘a little exercise book for felix sebastian otterbeck…’)

The inner world of music became for Surendran more real than the so-called outside world, and as he retreated into it he began to discover its profound emotional depths:

when i was ten i sat practising the piano with, perhaps, a chopin score in front of me and tears streaming down my face. the music was so beautiful that i just sat there trying to understand it and didn’t play games with my friends, or football – or do the things that boys normally do. i decided to dedicate my life to finding out why i found this music and that of many other composers so moving. now i know why. keats said that art is truth and beauty, and never was a truer word said. beauty does not however only mean beauty in the ‘positive’ sense – (i despise positive thinking) – but it can also encompass sadness and pain and the whole wealth of human emotions that makes life human and humane. (‘is one allowed to dream’)

His second piano teacher at the Bulawayo Academy of Music was Anthony Walker, who had a “slightly stricter approach and a more disciplined method for practising”:

he prepared me to the point where at the age of 14 i was able to win a scholarship to the royal college of music in london – a wonderful opportunity for me to further my music studies but also, and perhaps more importantly, an opportunity for me to escape the terrible civil war (what war is not terrible?) that waged in zimbabwe at the time, where amongst other atrocities 16-year-old youths were enlisted to fight (frequently being killed doing so) so-called terrorists sometimes against their own political ideals. i myself as a confirmed pacifist would undoubtedly have landed up in jail (or worse …). (‘a little exercise book’)

By the age of 14, Surendran held Licentiates in Piano from the Associated Board of the Royals Schools of Music (ABRSM) and Trinity College of Music and good ‘O’-level passes from school. With the aid of the scholarship from the ABRSM, he went to London (on his own) in 1977 where he completed an Associate of the RCM diploma, a Fellowship of Trinity College diploma, and ‘A’-level exams. (‘cv2001englishfinal’)

B.Mus. degree

In 1978, he enrolled for a BMus degree at the Royal College of Music, where his teachers included Bernard Roberts and Yonty Solomon (piano), George Malcolm (harpsichord), Virginia Pleasants (fortepiano), and Anthony Milner (harmony and counterpoint). Bernard Roberts was a great Beethoven interpreter, who hated contemporary music. To Surendran this was, however, “the language of my time and spoke to me with a directness that i failed then to perceive in earlier music”, and so they clashed violently:

it was often the case that after my weekly lesson the next student would wait patiently but fearfully outside the room long after his scheduled time peeking apprehensively through the glass window in the door and deciding that it would be safer to stay outside once he noticed a livid, red-in-the-face professor roberts passionately arguing with (while gesticulating almost to the point of attacking) a 15-year-old boy who coolly sat on the piano stool venturing his typically ironic and sardonic, even sarcastic remarks. (‘a little exercise book’)

Although Surendran acknowledged what he learned from Roberts about technique, his next teacher, Yonty Solomon, was more amenable; gentle rather than autocratic, coaxing rather than dictatorial. After only three lessons:

he told me – though i was only about 17 or 18 at the time – that i was already a finished pianist, implying that he did not want to interfere with the interpretative abilities and performance skills i had by then developed. from that moment on i never felt i had to play anything for him – as in a kind of audition or test – but did so only if the moment seemed appropriate – and we spent a year or so having profound and for me highly illuminating conversations about music and art in general. (‘a little exercise book’)

While at the RCM Surendran also took harpsichord master classes with Fernando Valenti, Gustav Leonhardt, and Christopher Hogwood.In June 1979 he won first prize in the Commonwealth Overseas Section of the Royal Over-Seas League Music Festival in London and soon afterwards participated with the other finalists in a recital at St James’s Church, Piccadilly where he play his own recently composed Piano Sonata. (‘Finalists of the Royal Over-Seas League Music Festival – Programme’).

He completed the BMus in 1981 with “second class honours, upper division” (‘BMus degree certificate’), and the same year enrolled for a Masters degree in Musicology at King’s College, London, studying with Brian Trowell, Reinhard Strom, Pierluigi Petrobelli, and Thomas Walker. The foundation of his abiding interest in historical performance practice, which became a feature of his career as a performer, composer, and teacher, was undoubtedly laid here. By 1981, he had composed 15 works and sketched out a number of others. Counterpoint, whether tonal (Baroque) or atonal (Serial), features prominently in them.

Such bald facts about Surendran’s studies in London do little justice to the enormous impact the city made on him and the personal freedom the UK afforded him, despite pressure of academic work and all-night practice sessions. His letters and other documents from this time as well as references he made later on, prove that this was a seminal experience.

He was exposed to some of the best performances of music anywhere in the world, had some of the best teachers in London, and among other things he spent hours in the Reading Room of the British Museum (where he studied Mozart’s manuscripts), steeped himself in the feast of concerts on offer, played in a gamelan orchestra, wrote poetry, composed, performed in some of the most prestigious venues, and revelled in his new-found friendships and emotional attachments.

One of his closest friends at the RCM was composer Keith Burstein, who wrote of his first impression of Surendran, around 1979:

He seemed to be someone living at some higher speed and intensity than anyone else around him and so when he actually stopped to speak to you it was like the kindness of a God for a mortal who just moved and did things in the normal way. I was immediately struck by his exquisite hands with their elaborate gestures and the pristine speech, more English than the English. Even in a vortex of eccentric characters, he set standards of is own. The shock of black curly hair, gold teeth and bright eyes like jewels all added to the drop-dead exoticism. You felt not ‘who is this?’ but ‘what is this?’ He floated quite apart from the college mob, in some stratosphere of his own.(e-mail to Heike Asmuss, 17 November 2013)

Burstein testifies to two other aspects of Surendran: his love of literature, and his ambiguous sexuality:

He was an ardent disciple of Herman Hesse and introduced me to his writings. He particularly loved Siddhartha and the serene world of the book will always emblemize an essence of Surendran for me and represent a wonderful moment of dream-like magic from my youth. We were all discovering and exploring our sexuality and although our [own] relations remained platonic we shared a sensibility that was dominantly gay. But Surendran seemed more complex than me in that regard, apparently able to have sexual relations as readily with women as men.

Another close friend in London was flautist and composer Martin Feinstein, for whom Surendran wrote three works. He also set to music two poems by Martin’s mother, novelist and poet Elaine Feinstein. He often stayed in the Feinstein’s house, where he enjoyed the artistic atmosphere of music and poetry. Strongly nurtured in childhood, his passion for literature developed into one almost as great as music, and in later life he wrote extensively: poems, essays, memoirs, and extended ‘compilations’ that mixed writing by himself and others with images and music. (See Surendran the writer)

Return to South Africa

Surendran spent six years in London and was still only 20 years old when he left, because his student visa had expired and could not be renewed. It must have been a very tough call having to leave Britain before finishing his Masters degree and head for apartheid South Africa, where he had never lived. He went to Durban (where his parents were now living) and took up a Lectureship in the Music Department at the University of Durban-Westville (UDW).

UDW had been established in 1961 as an ‘Indian University College’ under the Nationalist Government’s ‘Extension of University Education’ Act of 1959, becoming a fully-fledged university in 1972. Surendran abhorred this and all other aspects of the racialized state under which he was forced to work, especially the derogatory word ‘Indian’ by which not only the university but he himself was categorized, and characteristically always refused to deal with his experience of racism, whether institutionalised or not, as if it were in any way normal.

As a close colleague of his at UDW who first met him at this time, I remember that he dealt with apartheid primarily by sublimating his humiliating daily experience of its brutality and stupidities through hysterical fits of humour and rage; by treating it as if it were a surrealist, nightmarish joke. (the author of this biography, Christine Lucia)

Writing an editorial preface to a collection of short stories about the apartheid era written many years later by his father, Surendran put it very simply:

i personally reject all racial definitions such as the words ‘white’ or ‘black’ because they are artificial categories and have no real meaning, merely in my opinion encouraging racist thinking. u could line up a hundred people ranging in colour subtly from the darkest to the lightest and it would then be impossible to say where ‘white’ begins and ‘black’ ends. (‘is one allowed to dream’)

Early career

During Surendran’s three years at UDW he taught harmony, counterpoint, analysis, and music history. He performed frequently, among other things playing the complete cycle of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (‘the 48’) in 1983 on harpsichord, spinet, and clavichord, over four consecutive days. He continued composing at UDW and inter alia wrote the six baroque suites (1983-85), pastiches of Bach’s keyboard suites. They are slightly too ‘modern’ to have been composed by Bach and are written in a spirit of homage, following in a long tradition of European composition ‘in antique style’. In a recorded talk he gave in 1990? Surendran described himself as “composing in bygone styles so authentically that the resulting works could almost be rediscovered manuscripts from a past age” (dance of the rain programme note, 1987). The pieces he wrote between 1978 and 1985 display a mastery of pastiche techniques: Renaissance and Baroque counterpoint, Lisztian romanticism, Mozartean classicism, Webernesque serialism – all of this alongside a strong assumption of the importance of improvisation.

In the field of South African composition in the 1980s, the postmodern technique of quotation or pastiche was unusual. In a programme note from 1985, Surendran explained his six baroque suites as the fruits of a performer’s “intimate, intense and fulfilling relationship” with the music of the past, “the tangible evidence I have brought back with me of my travels in the Time Machine”. When he typeset the suites in Sibelius in 2006 (from the 1983-85 handwritten manuscripts), he wrote a ‘preface’ in which he seems to counter an argument that could well have been presented against such musical time travel:

some people would consider it a kind of inverted anachronism writing baroque music in the 20th century – like wearing a digital watch in a shakespeare play – or rather the other way around – wearing a cod-piece to a modern-day rave. it’s a thing of the past – it doesn’t belong to our day and age. but why? one of the advantages of our day and age is that it is so historically rich. we can live in the past just as much as in the present. those of us who are sci-fi enthusiasts even spend a large amount of our lives in the future. (‘preface’ to ‘six baroque suites’, 2006)

At the beginning of 1984, Surendran went to New Zealand to join his former girlfriend from the RCM, with a view to immigrating. Things did not work out, however, and he returned to Durban and continued teaching at UDW. He collaborated in several productions with a colleague in the Drama Department, Jay Pather, notably on The Trial Of Dedan Kimathi, a play by Micere Mugo and Ngugi wa Thiongo (directed by Suria Govender). “I choreographed and Surendran composed”, Pather recalls. “He was meticulous in the research of the Swahili and incredibly generous with his ideas, sensitive and demanding at the same time in his musical direction … an effervescent personality, a curious mind, a highly creative temperament and tautly disciplined” (e-mail to Heike Asmuss, 20 June 2014).

Surendran entered the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) Music Prize competition in Johannesburg in January 1985 and won first prize in both the piano and harpsichord categories – the first person ever to do so. He was awarded the Marc Raubenheimer Bursary, but not the overall first prize, and was invited to play his final-round works, Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 and the Frank Martin Concerto for Harpsichord elsewhere in the country. He continued to give other concerts in 1985 while serving out his appointment at UDW.

Natal Performing Arts Council (NAPAC)

At the beginning of 1986, he became resident repetiteur and composer for the Natal Performing Arts Council (NAPAC) ballet company in Durban, and in this post, with the encouragement of NAPAC Dance Director Ashley Killar, he began to write compositions using electronics and to further develop his interest in jazz and world music. One such piece was the dance of the rain, 1987, which “explores the rich palette of the DX7 synthesizer as well as the contrapuntal possibilities of the 16-track tape recorder” (dance of the rain programme note). It was a work that the Southern African Music Rights Organization (SAMRO) took to the International Society of Contemporary Music (ISCM) World Music Days’ in Warsaw in 1991, when SAMRO was attempting to revive its ISCM membership.

Gerald Samuel, who worked with Surendran at NAPAC, recalls his first choreography, to Surendran’s the incredible jazz machine (1987), part of the ballet three minutes to midnight:

I think we toured to schools in 1987 or 1988 … It was made up a series of danced poems from the English curriculum that matriculants would have known at the time. I wanted to create something new and accessible to high school pupils about a much wider understanding of Dance than ballet. Ashley unreservedly agreed with me. One of the poems was ‘The unexploded bomb’. The whole thing was very avant garde for its time I would say. Consider that tours to schools would have mostly been extracts from Coppelia and demonstrations of pointe work from Swan Lake. (e-mail to Heike Asmuss, 31 March 2014)

It was at NAPAC that he met prima ballerina Linda Smit, whom he married in 1987. After their daughter, Lîla Francisca Reddy was born in August 1987 they moved to Johannesburg, where Surendran headed up the music department at the Federated Union of Black Artists (FUBA), an independent arts academy for mostly underprivileged students. By that time, Surendran had already got involved in the fight against apartheid in the artistic field and was active on various committees. In order to make a point against existing prejudice, he rapidly enabled a talented young pianist, Joseph Mosheshe to get a bursary for overseas studies. Moses Molelekwa, another student of his, later became a famous jazz pianist.

Teaching

At FUBA, as well as in the early 1990s, as a guest lecturer at the University of Namibia, Windhoek, Surendran not only taught classical music and academic subjects but also jazz, rock, pop, music technology, and especially composition, which later became his main teaching interest. He used his ‘10 principles of clazz’ as part of his teaching method, encouraging and inspiring the students to work in a free and open way and organized exciting public concerts in which students would perform and present their work in a ‘real’ performance situation.One of his students at the composition seminars he taught at the University of Namibia was a German teacher on a temporary contract there, Heike Asmuss. She remembers that “professional musicians sometimes played as a backing band for beginner students, making even a simple piece sound great, and the experience became a highly motivating one for the student”. Heike was to become an extremely important person in Surendran’s life.

In a job application in 1997 (using capital letters – this was a ‘formal’ document), he wrote:

I have always had an intense interest in education and dedicated part of my work in South Africa to redressing some of the wrongs perpetrated by the effects of apartheid in education. Having been fortunate enough to have received a good musical training elsewhere I felt the need to share something of what I had myself learned with some of my less fortunate compatriots. It has indeed been a privilege to work with people whose thirst for knowledge is like that of a desert plant for water. My approach to music education has been very biased towards creativity and indeed one of my most exciting pedagogic experiences has been dealing directly with the creativity of others in my composition seminars. I prefer the seminar system in that the role of the lecturer is decentralised and responsibility is shared by all members of the group. I believe firmly that students learn as much from each other as from a teacher and am not partisan to that approach where information given in a pseudo-authoritative manner is merely absorbed in a purely passive way by the students. I also believe in constantly being in touch with students’ changing needs as opposed to adhering to an outdated syllabus no longer appropriate within a given social context. I feel that it is much more of a challenge for a teacher to be capable of adapting to students’ needs and to be sensitive to what is really relevant to them and at the same time to be able to guide them into unknown regions that can only broaden their horizons than to foist upon them willy-nilly what she/he may have grown up with two decades earlier.

Channel 18

By the time he left FUBA at the end of 1989, Surendran’s marriage had ended. He was by this time well established in the music industry in Johannesburg and famous around the country as a ‘crossover’ musician and “militant muso” who expressed anger about “South Africans [who] are not very well educated about classical music” and “people associat[ing] classical music with whites and boycotting it”, while at the same time he was “constantly expressing outrageously irreverent ideas like ‘The tune of Tina Turner’s You’re Simply the Best is very similar to Wagner’, and ‘Jazz and rock musicians are just as talented as classical ones’”. (interview in Cosmoplitan, July 1990)

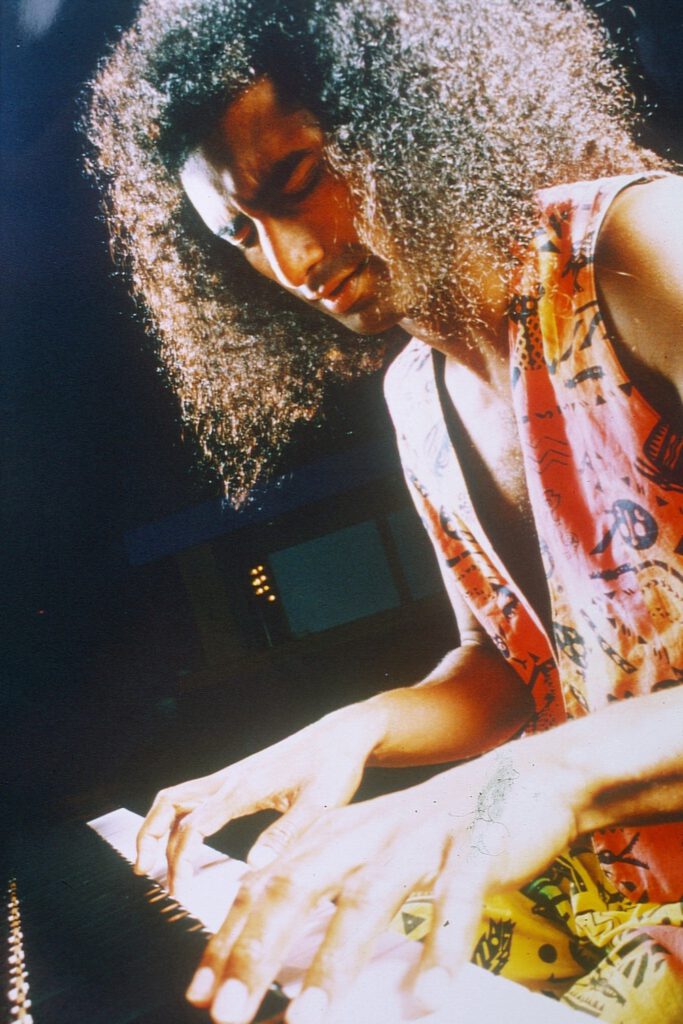

At the beginning of 1991 he formed a jazz trio, Channel 18 with Danny Lalouette on bass and Rob Watson on drums, to which a soloist such as Bruce Cassidy – on electronic valve instrument (EVI) – was often an additional player.

Channel 18 gave memorable renderings of original compositions where Bach or Mozart were heavily woven into the fabric of the music and where Surendran’s virtuosity found a tremendous new outlet. They rarely played jazz standards, and one of the few other composers they played besides Surendran was Claude Bolling. (See Surendran as performer)

“Jazz in its nature is a fusion of disparate elements”, wrote a critic in the Pretoria News on 9 June 1992. “Some jazz musicians freeze the fusing process by restricting themselves to the confines of a particular idiom. Others celebrate it by pushing boundaries. Channel 18, shaped by vitality, superb technique and the genius of Reddy, belong in the latter category.”

First composition commissions

By 1994, year of South Africa’s first democratic elections and the instigation of a new ‘Government of National Unity headed by newly elected President Nelson Mandela, Surendran Reddy had attained widespread fame in South Africa as a composer-pianist brilliant in both classical and popular music. He had directed musical shows presented by the four different Arts Councils of South Africa and had performed concertos such as Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 in 1991 and Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F Major in 1992.

He received his first commissions from SAMRO: in 1992 for go for it! a work for solo piano and in 1993 for à la recherche de la paix et de la liberté, a piece based on arrangements of ‘Nkosi Sikelel’iAfrika’, ‘Ntiyilo-Ntyilo’, ‘Mannenberg’, and ‘Mayibuye’. Surendran’s main theme as a composer during the 1990s was freedom, and combining a diversity of musics was his compositional strength. He expected people who played à la recherche to be familiar with both classical and jazz pianism. “For me, a musical score bears the same relation to the actual music in sound as does a map to a landscape”, he wrote at the beginning of the score:

For this reason it is relatively uncluttered by interpretative detail. Like a Baroque composer, I rely on certain conventions of performance practice being generally understood in order for the score to be correctly interpreted. It would therefore be a help for the potential ‘classical’ performer to listen to jazz recordings as well as live performances to familiarize herself/himself with the general ethos of such music. (‘Composer’s Note for the Performer’, Samro score of à la recherche de la paix et de la liberté, 1993, page?)

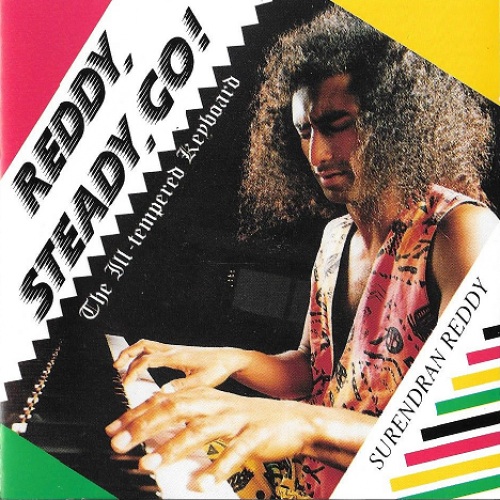

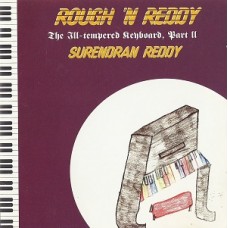

Surendran recorded two solo CDs in Johannesburg, Ready, Steady, Go! (1994) and Rough’n Reddy (1996), wonderfully illustrate his crossover style, one of the conventions of which (as with playing Chopin) is maintaining a steady beat in the left hand “while the right hand moves rhapsodically, and with possibilities of rubato, above it” (‘Composer’s Note’).

On these two CDs, Surendran plays improvised jazz arrangements that weave Bach, Mozart, the Beatles, and Andrew Lloyd Webber into tumultuous solo piano narratives.

Germany

In August 1994, Surendran accompanied Heike Asmuss back to Konstanz, Germany, where she had been living before she went to Namibia. He joined her permanently in January 1995 and began trying to to establish himself there while continuing to work in South Africa whenever he could.

SAMRO commissioned him in 1996 to contribute a section to a projected multi-authored Human Rights Oratorio for the Olympic Games in Atlanta. Although the Atlanta performance never happened, Surendran’s section, Masakane – Let us build together (for voices and orchestra) was eventually premiered in Durban, in March 2000.

Two other SAMRO commissions from this time reflect the ideals of the ‘new nation’: Toccata for Madiba (1997) and Mayibuye Suite (2001), both for concert organ.

From his new base in Konstanz, Surendran built up afresh his reputation as a teacher, giving workshops, master classes, and individual lessons in piano, electronic keyboard, composition, and improvisation (classical, jazz, pop, rock), not only in Germany but also in Switzerland, the USA, and back in South Africa. He also performed internationally during the 1990s, for example with Kiri Te Kanawa at Sun City, South Africa (1995), at the Zeltfestival Konstanz and for Deutsche Welle, Cologne in 1996, and with the SABC National Symphony Orchestra in Amman and Cairo, also in 1996. Both with Channel 18 and as a solo pianist he was a regular artist at the National Festival of the Arts in Grahamstown, South Africa from 1991-1996.

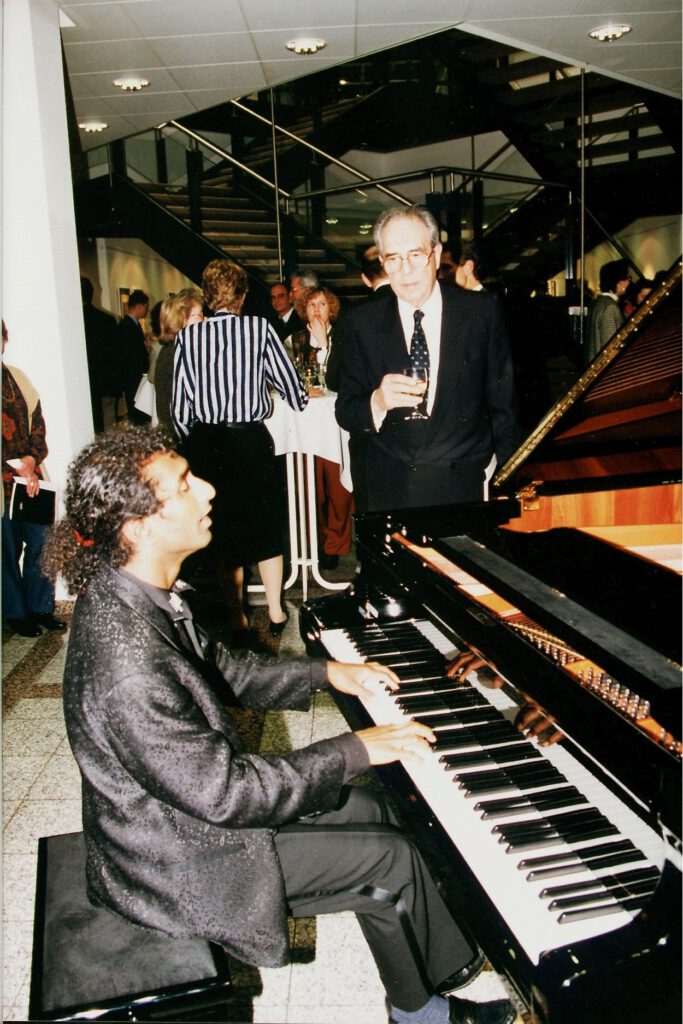

He played at the Stadthalle, Muenchen-Germering, Germany in 1997, for the opening of the Kulturzentrum, Konstanz in 1998 with a performance of Masakane, and for the Aachener Kulturtage in Aachen and at the ‘Harmonie’ jazz club in Bonn in 1998.

He and German composer/keyboardist Andreas Apitz appeared at the Frankfurter Musikmesse in 1996 and 1999 with their duo Campaign for Real Time, he played for the musical Little Shop of Horrors in Konstanz in 1998 and 1999, and he performed and lectured at the Dana New Music Festival, Youngstown, USA in 1996 and 2000.

These are only a few examples of the concerts listed on Surendran’s concert lists for the late 1990s. It was exhausting work, alongside the struggle to adapt to living in Germany, where his experience of racism was even greater than it had been in South Africa. So much so that during 2000 he more or less gave up his career as a public performer, because of ill-health.

Surendran as performer

Surendran’s career as a performer of classical piano, harpsichord, jazz piano and electronic keyboard lasted 25 years. It began at the age of 13, and already by the age of 16 he was selected by Fernando Valenti to play the harpsichord in a recital of Scarlatti’s music in the Wigmore Hall, London and at 19 performed the whole of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier(‘the 48’) in the Museum of Early Instruments at the RCM. This was the year (1981) when his teacher, Yonty Solomon, said of him, “Mr. Reddy is one of the most brilliant talents to have been at the Royal College of Music”. (‘To Whom It May Concern’, 20.6.81)

As a classical pianist he did not stick to the conventions of his time: he preferred a score in front of him, carefully prepared for his own page turning, and he rarely wore tails let alone a suit, and once even performed a classical recital barefoot and in shorts. (It was a particularly hot day.) He was an outstanding sight-reader and memorizer, learning a whole concerto from the score, while he was at the RCM:

i entered into a wager with some of my fellow students that i would learn a concerto without once touching the keyboard but would do everything entirely mentally. the first time i would play the concerto ‘in the flesh’, as it were, would be at the first rehearsal with the orchestra, a couple of days before the final concert. it was frank martin’s harpsichord concerto and i did just that: i studied the score, worked out the fingering, which when necessary i would write into the score, memorized it, practised it mentally – all in my head – without once touching a piano keyboard – and then went along to the first rehearsal and played it successfully with the orchestra. i won the bet. it did of course require a tremendous mental effort but it was possible – though i wouldn’t recommend learning every work in this way. i wanted to prove a point however, and it worked. what i am trying to say is that this part of our mental faculties – the imagination, the rarefied realm of pure intellectual thought, analysis, the inner ear, etc. constitutes an incredibly powerful tool … the tactile sensuality and physical corporeality of actually playing the music are of course wonderful assets, but they can sometimes also be a distraction to an authentic understanding of the music. practising in your head is sometimes even more beneficial and effective than doing so physically with your real fingers and your real ears. (‘a little exercise book’)

He is remembered by audiences primarily as a performer of stupendous technique. He played some of the most difficult classical music in the repertoire, from early music to late 20th century music, and he improvised jazz with wild abandon. “It’s like watching an ice-block melt in the microwave”, a Cape Town critic had written of his pianism during the 1990s. “This man is hot.”

Bruce Cassidy remembers playing “some amazing and difficult music” with Channel 18:

After one of my own gigs at the Market Theatre Surendran came up to me and said, ‘you know that thing you do where you change octaves and trill a minor 3rd’ (he was referring to a trick of performance on the EVI, a wind controller that I play) – ‘well I’m going to try that on the piano’. Sure enough the next time we played together he played it for me. I was amazed that he could do it and told him so. It was certainly not idiomatic to piano technique. Then he said ‘I want you to write something for me that’s impossible to play’. I remember thinking and I still think ‘what an indomitable spirit, what an example!’ (E-mail to Heike Asmuss, date?)

For his solo jazz improvisations Surendran developed intricate and virtuoso left hand patterns to represent the bass player and drummer – he was remarkable for the virtuosity of his left-hand, unusually so for a jazz pianist – over which he would freely improvise with the right hand, combining advanced harmony with extended melodic improvisations. Although his jazz tunes can be published as lead sheets, transcriptions of the improvisations he played on those same tunes make spectacular keyboard solos.

It was almost a point of honour for him to give himself utterly to whatever music he was playing at the time:

in the past i used to say to my students: imagine you will die after each note and it’s your last chance to say everything you wanted to say, maybe that’s a bit too extreme but man muss permanent nur den moment geniessen, zum vollsten [transl.] … i see an instrument as being an extension of the soul, you have to breathe your soul into the instrument in order to make it speak. … it’s the soul that actually makes the instrument speak. (‘three afternoons with surendran reddy’, 2009)

Surendran did not view performance as a ‘recreative’ act and composing as a ‘creative’ one. There is, he said, “no real difference between [them]. a good actor has to get into his role with such authenticity that he becomes the character he is portraying. an interpreter has to get into the mind of the composer with such conviction that for that moment he is Mozart, Sibelius, Palestrina” (‘preface’ to six baroque suites).

His commitment to music was the same whether he was playing a classical concerto or gigging at a corporate function.

Surendran on recordings

Surendran’s playing is preserved on hundreds of recordings, made from the late 1970s until he died in 2010.

Some are studio quality, some are records of live concerts, some are audio files that he made by re-notating Sibelius scores as he finished a piece in order to get the best idea of a composition, while others are home recordings, which often carry with them the intimate aura of spaces he lived and worked in, and the homes of friends.

Surendran as composer

Surendran composed prolifically, leaving well over 100 titles by the time of his death. Many pieces are for keyboard and many espouse his philosophy of clazz; and although only a few were reproduced (by SAMRO, as commissioned works), some his music has been disseminated worldwide and there are several performances on YouTube and Sound Cloud. By 1994 already Surendran had received several international performances: his four romantic piano pieces were choreographed by Reid Andersen for Alberta Ballet, Canada; the electronic ballet score the dance of the rain was played at the ISCM World Music Days in Warsaw; à la recherche de la paix et de la liberté was premiered in Moscow. And live performance of his music still continues, around the world.

my favourite times were always the transition from daylight to dusk and the gradual transformation from dawn to day when the air seems to shimmer and beckon with promise and unfulfilled dreams. when i compose i get most of my ideas in that in between state twixt dreaming and waking, a semi-consciousness in which u are not too deeply in sleep not to be aware of ideas and not too awake in order to be grounded by the exigencies of rationality and the sometimes harshness of day to day realities. a world of dreams, ideas that flit like butterflies through your head and need to be caught gently with nets made out of gossamer, as ephemeral yet strong as the (thread?) web that a spider spins, a world in which we are in contact with our Creator. before this passage gets more purple (or even pink) perhaps i should mention that this state can also be achieved after the third double scotch or a couple of good brandies. my ideas appear to me as melodies or chord progressions or rhythms that are just poured into my head from i know not where and the development of them into a fully-fledged piece of music, a sonata, an etude or a set of variations is simply compositional technique – an acquired knowledge leading to the ability to realise the potential intrinsic within these gossamer ideas. the nature of inspiration, as in love, must have something divine and inexplicable in it. (‘the life and opinions of surendran reddy, gentleman?’, 2009)

the 10 principles of clazz:

- i devised the term “clazz” to describe my musical style, compounding the words classical and jazz, which formerly in music history denoted styles that were kept quite distinct from each other, but in recent years have been moving closer together. in effect the term clazz encompasses for me a fusion of many different styles of music. my ears are open to all musics in the world.

- surendran’s law of harmony: every note can be harmonised by every other note.

- surendran’s law of rhythm: every note should be neither shorter nor longer than is necessary in its compositional context.

- rather than a bar being of a predetermined length which is then filled with notes (in many cases either too few or too many) it should arise organically from the melodic, rhythmic, harmonic and aesthetic exigencies of the composition, does not have to remain constant and is therefore always of exactly the right length.

- just as one can observe a landscape containing different elements from varying perspectives (above, below, right in the middle of it, etc.) and move around within this landscape, so can one conceptualise a musical composition, working not with images but with sound. in this way i conceive of compositions as soundscapes.

- every compositional idea contains within it the potential for its own development. all that a composer has to do is realise this potential.

- learn to cook!

- start with perfection – and improve on it …

- surendran’s “one man one note” law:

basically u have 3 possibilities (a trilogy in 4 parts – cf. douglas adams)

(i) finding the right time for the right note

(ii) finding the right time for the wrong note

(iii) finding the wrong time for the right note

(iv) …

10. u can stand on the outside looking in to the music, or u can be on the inside looking out of it …

(‘introductory notes’, toccata for john roos, Samro, 2008)

The first four principles deal with music directly, but the rest are philosophical comments addressed to young composers, the most unexpected being ‘learn to cook!’ although it is not surprising, however, for Surendran’s mother is a wonderful cook, he loved to cook (vegetarian food, as a confirmed pacifist), and his daughter Lîla has trained as a chef. Cooking for him was as creative as any artistic act.

The dominant style within his clazz style is often mbaqanga, sometimes obsessively so, occurring in his jazz arrangements with such frequency that he suggested ‘mbaqanga’ be an expressive direction in lead sheets, like ‘swing’ or ‘bossa nova’. It was as a soloist and as leader of Channel 18 that Surendran played best as a jazz pianist, and maybe the obsessive syncopation did to always work in conventional accompanying situations.

His philosophy of clazz, however, was more than a musical impulse or an obsessive pianistic reflex; it reflected his “general philosophy, which is one of openness to all cultures and peoples of the world”. (‘short bio john roos’, 29 September 2007). From the 1990s, he says:

i began to embrace the musical diversity inherent in world musics and came to realise that all of this rich heritage could also be incorporated into my voice and become part of my musical language if i so wished. rather than being born into a culture and almost becoming a victim of it one could choose ones culture or cultures and integrate one’s perception of them into one’s own creativity. both in time and in space one could travel around our world absorbing the best that different cultures and epochs have to offer us and making this, if appropriate, our own voice. i came to see music as one language with countless different dialects when viewed both internationally and inter-temporally any of which could be incorporated into one’s own self-expression if the subject matter of what one wished to express so necessitated it. (‘preface’ to ‘six baroque suites’, 2006)

Music of the rainbow nation

Both with his ability to cross between repertoires and styles of playing and in his own composition, Surendran arguably took South African classical music out from its colonial, formerly privileged ‘white’ comfort zone and gave it a new status as a fusion of ‘white’ classical and ‘black’ popular music. His compositions in many ways epitomise the ethos of post-apartheid South Africa, certainly the initial few years in which Archbishop Desmond Tutu famously dubbed the country the ‘rainbow nation’.

However, just as he was able to live and work more freely in a new and ostensibly non-racial South Africa, Surendran left it to settle in Europe, and suffered the fate shared by many composers who straddle two countries, that he never felt at home in either; and unlike many other composers, neither South Africa nor Germany was his ‘homeland’ in any nationalistic sense. Indeed, he vehemently rejected nationalistic and patriotic sentiment. His immediate working environment became all-important, a space where he could be surrounded by books, music, his keyboard and equipment, and be himself. Here he was most truly ‘at home’.

Other works

Ever since he had moved to Johannesburg in the late 1980s Surendran wrote logos and jingles for the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), and when he immigrated to Germany he continued this kind of work. He also continued teaching in Germany, writing many short pieces and exercises for individual students. Among them is a 7-part exercise manual and treatise for piano that he called (modelling himself on Bach) a little exercise book for felix sebastian otterbeck. Grounded in western classical music, Surendran was inspired by a wide range of music including jazz standards, musicals, Javanese gamelan, African traditional music, and Indian music. The climactic ending of many of his flamboyant solo works is a series of runs or glissandi written in the polyrhythmic pattern of the ‘tihai’ often associated with the conclusion of an Indian classical piece.

The variety of his compositions is reflected in the List of scores and List of recordings (some of his works currently exist only in recorded form) on the Sales page.

Illness

In Konstanz Surendran met and become close friends with tabla-player Florian Schiertz, who had trained at the Rotterdam Conservatoire and spent many years in India. The two collaborated musically, giving memorable concerts of jazz-Indian crossover music in South Africa and Germany. Their South African concerts in 2005 were particularly successful: this was in many ways like a farewell tour, the last major performances he gave. Fortunately, the Stellenbosch University concert was recorded although the Wits University concert was, according to Schiertz, the finest performance.

Surendran’s interest in world music was as eclectic as everything else in his life. As he put it: “One of the great advantages for a composer working in a 20th and indeed 21st century context is the availability of art and culture from every corner of the world and the possibility of being influenced by this, without the exigencies of having to think (like a 19th century composer) about this phenomenon in a nationalistic way” (‘clazz prog note’, 29 September 2007).

Schiertz was keen to collaborate on recordings, but by the mid-2000s Surendran had already succumbed to what he described as “a difficult, hard-to-diagnose and debilitating nervous illness – which i have now come to think of as being incurable” (letter to Florian Schiertz, 28 February 2006). He spent years trying various allopathic and homeopathic remedies and seeking psychological help for something that was never satisfactorily diagnosed. His letter to Schiertz, uncannily echoing Beethoven’s ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’, explains the effect that living in Germany had on him:

during the time when i was building up i was forced simply to do any kind of work (in the music field of course) just in order to pay my bills – not really having a support system here such as a family or the kind of support that you automatically get when u are in your own country (provided it is not south africa in the apartheid times – and you do not have the wrong colour of skin). of course i – like everybody else – have my dreams – but my illness and circumstances have taught me that i can hardly dare to do this. as u always say: what to do? a person can only do what is possible under the circumstances. i have achieved some kind of inner peace with the conviction that – as mahler said: my time will come – and the best i can do at the moment is to dedicate whatever time i can whenever i am fit enough to do so – to my creativity. *i have nothing else* – i have lost family, my health, my own daughter, financial security, etc., etc. – in some ways terrifying though this is, i no longer have any distractions. the only major hurdle is my own poor health – but if mozart managed to dictate the notes of his beautiful requiem while dying to his favourite pupil – i can also manage from time to time to type a few notes into the computer.

can u imagine how acutely i feel the irony that after having created all this beautiful music i cannot even play it myself? … what if we get a recording contract? at the moment i *cannot* play – it is simply physically impossible at the moment. of course i can lightly tinkle away easy stuff like richard claydermann junk – maybe – for a few minutes (b4 my brain jumps out of my skull in sheer disgust) – but certainly not the stuff i write – which is already at the limit of possibility – as one of my goals as a composer was to expand and intensify the technical virtuosity of the instrument.

can u imagine how embarrassing it is when a compose can’t even play his own stuff? and also painful – cos once i could do it – well, sort of – but i suppose that is all part of growing old. we have to accept the limitations of the body and its frailty – we have no other choice.

but i’ll stop tiring u with this stuff – u’ll just think i’m feeling sorry for myself … there is nothing i would like more than to make recordings with u if it were physically and practically possible. but i can’t promise things when i myself have no security whatsoever in the state of my health. (Letter to Florian Schiertz, 28 February 2006)

Surendran Reddy’s relationship with Heike had been platonic since 2000, and in the 2000s Surendran became openly gay, fully aware of the impact this would have on those close to him, most of whom accepted it totally. The compilation books he put together during these years, as well as his memoirs and other writings, are outpourings – unashamed confessions – of explicit and riotous eroticism, humour, pain, philosophy, and much else. They give a revealing account of his values, his delight in word play, and his keen sense of the ridiculous.

Writing was, alongside composition, Surendran’s way of dealing with life, in his last years. (See Surendran the writer) Outpourings of music also continued. Surendran had for many years been a chronic insomniac, and he now worked day and night as the dates & times of many Sibelius files he left show, driving himself frantically while on medication, and imbibing too much alcohol, which numbed the pain but did not improve his state of health.

2006-7

In 2006-7 there was a particularly frenetic spate of activity, resulting in (among other things) the 5-part ‘trilogy’ comprising four of the most difficult piano works he wrote, initially called clazzical sonata in c, etude pour flore, etude for philipp, and requiem for a none, plus a piece for bass guitar and piano, back to the bass-ix (for stefan). These were written for his close friends Isabella Molina and her husband Michael Wiener, their daughter Flore and her partner Philipp Eden, who was like a son to Surendran, bass player Stefan Schoenegg and various other people including Reiner, one of his lovers. The overall title of the ‘trilogy’, by “surendran (quicksilver) (f)reddy“ as he styled himself, was “the importance of being reinest (a trilogy in 5 parts 😉 ) or a south african rhapsody? or a family affair, for oscar, douglas, hike, michael (no 1) and of course reiner and ALL rabbits Friends and Relations :-))”.

The clazzical sonata in c subtitled ‘the hammerclazz’ (after Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 106, which Surendran had played as one of the SABC Music Prize works in 1985), was commissioned for the NewMusic Indaba at the Grahamstown Festival of 2006 but was only completed a year later in 2007 – the first time he had missed a commission so spectacularly. It has three movements, dedicated to the classical composers he most loved: “(i) wolfi” (Mozart), “(ii) ludwig” (Beethoven), “(iii) frederic, and, of course, alexander” (Chopin and Scriabin). etude pour flore was submitted as etude for flore by the South African Section of the ISCM to the World Music Days committee for possible performance in 2008. etude for philipp became berceuse for philipp and flore, a work whose technical challenges push it towards the realm of conceptual music and which at one point was re-titled (approriately) the diabolic variations. And requiem for a none became toccata à la mode for mol(l)-in-a, a pun on dedicatee Isabella Molina’s name.

These later works, very difficult to play and encoded with allusions and quotations, are often littered with detailed instructions on the score and manic dedications that take up half the page. The most often-played ‘clazz’ work from 2007 is toccata for john roos, Surendran’s last commission from Samro, for the Unisa International Piano Competition of 2008. (This was won by South African pianist Ben Schoeman, who premiered the work at the competition.)

Surendran the writer

Although he had written intermittently all his life, between 1998 and 2007 Surendran wrote more poetry than ever before – playful, humorous, autobiographical, erotic, philosophical, political. There are for example a number of handwritten books of poems, the compilation no offense, and the poetic cycle the miaow, written in 2007 after a discussion with his friend Florian Schiertz about the Tao. This combines Dada and philosophy in a tongue-in-cheek way. It consists of 42 parts – 42 being the answer, Surendran wrote, to the

ultimate question about life, the universe and everything [in] one of my favourite books, douglas adams’s the hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy, 5 books actually – a trilogy in 5 parts as he referred to it, with his typical irrepressible sense of irony that came to my rescue time and time again in some of the darkest moments of my life; and that were always a sheer delight in some of its brightest (from ‘madiba: a novelette in sonata form’, 4 December 2007).

Profoundly ironic humour and tragedy were intimately connected in amost everything he said or wrote so that little of his writing can be taken purely on face value: it is immensely layered. He wrote philosophical and reflective texts about his humanitarian values, artistic and spiritual concepts, and epic poems, humorous or serious autobiographical texts, and he created multi-art-manuscript-books, which he spiral bound with a glossy cover and reproduced privately.

These multi-art books mix his own texts and those by other people with photos, designs, artwork, and music scores. One called 10 principles expressing my concept of art (2008) gives a deep insight into Surendran’s artistic visions. He describes in a half-fictional, half real introduction how this document was inspired by a personal encounter. Another one, a short hisTory of the past, the present AND the future (2008), is an unfinished manuscript about physical and mathematical phenomena, gravity and antigravity, time as a magnet, rationality and intuition, concepts of infinity, god and the universe.

truth, beauty, sadness, love and death (2007/08) is another multi-art-manuscript-book. It contains a text called ‘madiba – a novelette in sonata form’ which is a plea for freedom and humanity, and for respect towards artists. Passages about art and the situation of artists in society alter with autobiographical passages of Surendran’s own life mainly in South Africa during apartheid. The novelette is embedded in a composition of artworks, poems, a music score and many other ‘snippets’ revolving round the main topics of the book. the life and opinions of surendran reddy, gentleman? (2009) is a collection of memories mainly from early childhood but also from other periods of his life. it is autobiographical in nature but on many occasions also fuses fiction and reality in a playful poetic way.

The books Surendran left after his death are an eclectic assortment: all the books by Douglas Adams, lots of other SciFi, novels by Kafka, Coetzee, Breytenbach, Edmund White, and many others, poetry, non-fiction covering a large range of topics, some in German, which he spoke and read fluently, most of them in English. (And he had already left behind an extensive library in South Africa when he left in 1995.)

F-A-I-R-P-L-A-Y

Surendran Reddy was always full-on engaged and ‘involved’ – he was no recluse – and had a great deal to say about the position of an artist in society, about how little artists earn or are esteemed, and about racial intolerance. He earned little from royalties, despite being both an Associate Member of SAMRO and a member of GEMA (Gesellschaft für musikalische Aufführungs- und mechanische Vervielfältigungsrechte) and notwithstanding many international performances and broadcasts.

Like almost every composer-performer in Germany or South Africa he could not survive on royalties and performances, and hence teaching was at first his mainstay, before he was supported by friends, and on the dole. Being a member of organisations such as the South African Musicians’ Alliance and the Composers’ Guild, being many times adjudicator at the Roodepoort International Eisteddfod and the SAMRO Overseas Competitions enhanced his profile but provided no financial security.

Ever a champion of non-racialism and egalitarianism – he was a Committee member of ‘Hand in Hand International’, an anti-racism organization in Germany – Surendran formed an organization in 2008 called “F-A-I-R-P-L-A-Y”, together with seven friends, in order to campaign for a more even-handed treatment of musicians. “Artists are able to achieve significant goals through peaceful though sometimes of necessity confrontational means,” he wrote on his website www.surendran-reddy.com at the time, “making it fully unnecessary to waste one’s own life and the lives of other people in such stupidity as war and the ultimately meaningless accrual of personal wealth”.

It is clear from many of his writings and interviews that he believed the way society rewarded musicians to be totally out of proportion to the contribution they made to that society.

‘Three afternoons with surendran reddy’

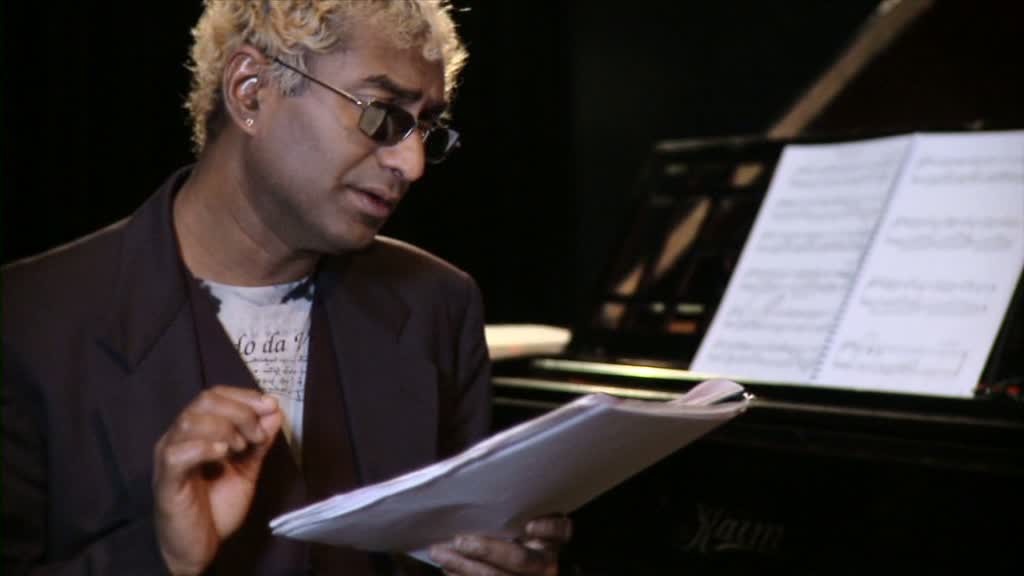

In 2008 director Béla Batthyany began filming Surendran for a documentary film. He continued in 2009, but the footage – and film as he originally envisioned it – remained incomplete at Surendran’s death in January 2010.

Heike Asmuss obtained permission to have the existing 9 hours of footage edited and produced into a 90-minute DVD called Three afternoons with Surendran Reddy.

On film, he mimics the dancing of one of his great idols, Michael Jackson, sports his blonde hair, and talks – at times with energetic humour, almost hysterically, and at times in deadly earnest – about music, composition, teaching, art, and life.

missa gratias per antonius

The last piece Surendran worked on, like his hero, Mozart, was a requiem mass, of which extensive drafts of each movement survive. Unlike Mozart’s Requiem, however, it is a joyful and exuberant piece.

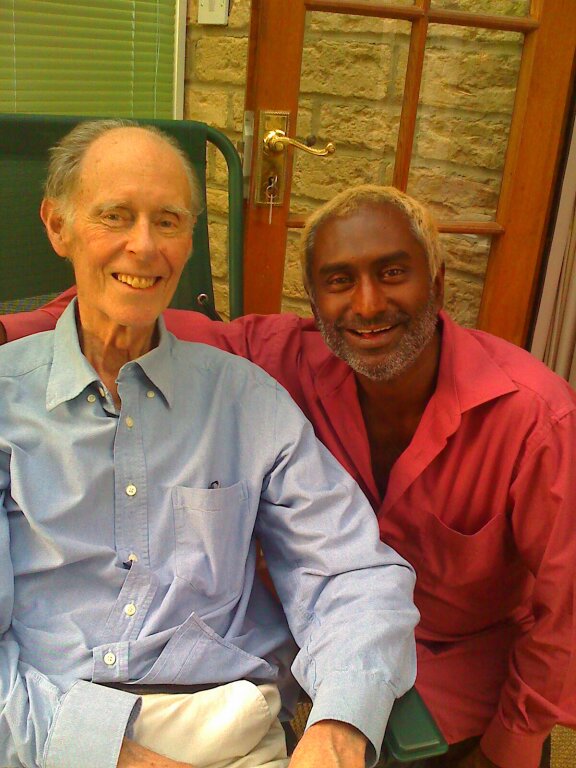

missa gratias per antonius celebrates the life of Surendran’s former teacher, Anthony Walker, although the piece also goes way beyond that, to become a celebration of ‘life, the universe, and everything else’ (to quote Douglas Adams).

Heike Asmuss and Surendran visited Walker at his home in Oxford (a place Surendran loved) in autumn? 2009, where they had a long discussion which Surendran recorded.

Both of them were quite ill: Walker died in December 2009, which devastated Surendran but also gave him a sense of urgency to complete the missa.

This was however still incomplete when Surendran Reddy died, in hospital in Konstanz on 22 January 2010. Heike Asmuss was at his bedside.

life and death of a tree* one day i went down to empty the garbage cans downstairsit was the organic matter that is used as compost in countries like in south africabut that is simply discarded here in germanythey have a very complicated system here of which they are very proudbecause of course germany is the leader of the umwelt (environmental friendly) movementwhich is why when u travel by air over parts of the ruhrgebietu c sections of forest destroyed beyond rehabilitationand u still get acid rain hereat any rate so much for that.rubbish has to be separated into its component partswhich means technically that something as simple as a tea-bagafter it’s been usedhas to be divided up into the metal staplethe paper used for the label which is more like cardthe infusion paper in which the tea leaves are containedand of course the organic part – the tea leaves themselvesfor simple people like me this is so complicated and takes so damn long(when i have time between filling out forms, paying or not paying bills, fighting with german almost kafkaesque bureaucrats and having sweet, loving talks with my lawyerherr professor dr sebastian boesingor or is it professor dr herr boesingone of the best, if not the best)then i try to compose music, write poetry and books about the people, animals and trees i love.at the moment on a good day i’m just about managing one line a daybut this is being reduced at an alarming rate to practically one word less per dayand when i reach just one word – i might just start looking for another job.i doubt whether many people would be interested in poetry consisting of one letter per poembut at any rate i could never be accused as was my dear colleague amadeus of writing too many notesof being guilty of writing too many letters, words, sentences, pages, books, volumes etc.another way of looking at it of course could be:save the trees. i’m sorry i made a mistakeit was heike, for it was she who had taken the organic waste downwho had discovered the baby squirrelwhich in better days if we were lucky we had seen prancing playfully through the trees at the back of the houseshe quickly closed the bin rushed up and through sobs explained what she had seenwe had just been fighting before and the squirrel brought us togetheri tried to comfort her and tried to be manful about thingsnot so easy for a gay guyand we both agreed that it was both denigrating and humiliatingfor a once vivacious and delightful living beingso full of fun and charmto be thrown like a piece of rubbishon a heap of rotting leaves as compostso we decided to give him a decent burialand then we realised what had happened.the tree that used to be his home had been chopped downand either he fell to his untimely death lost his parentsor just generally succumbed to the trauma of it allour own personal chain saw massacrelocating the place where the tree had been i dug a hole in the groundgently lay him inand hike and i uttered some words we felt were appropriatewe did not know whether he was a catholic squirrela muslim onea hinduso basically we just muttered some mumbo jumbobut what more can one do?and the treewhat it had seen over the yearstwixt lake constance and our slightly dilapidated “grusel haus”because it looks a bit like one of those old haunted housesnot scary though, with character and charm,we shall never know.perhaps it is a table now, or a chairor just burned as firewood and all that remains are dust and ashesis this what is known as reincarnation, karma,perpetual transformation but often into something worseu can keep itbeethoven in his diabelli variations takes something worse than worseand transforms it step for stepuntil we reach the heavens and beyond.give me art, any time 😉

*from ‘life+death’, 20 February 2008