This Critical Edition of Music by Joshua Pulumo Mohapeloa collects together for the first time all extant works published or in manuscript, by J.P. Mohapeloa (1908-1982). Download the General Introduction to the Mohapeloa Critical Edition to read about this edition in more detail. See also Mohapeloa: Mohapeloa Biography and African Choral Music: Music’ elsewhere on this website.The bulk of this Edition constitutes the newly prepared and edited vocal scores, but there are also editorial notes and translations, as well as pages of contextual information, including photographs.

The works of J.P. Mohapeloa are presented in this Edition in rough chronological order by original date of first publication, with a few miscellaneous unpublished items towards the end. (See ‘Catalogue: Overview’ for a comprehensive list of works.) Song titles are always given in italics, as are titles of the collections they come from. Although it is common practice in musicology to put individual titles in scare quotes and titles of song collections in italics, both kinds of title are given in italics here because none of the collections constitutes a ‘cycle’ intended to be performed as a complete entity: indeed, these works are only known individually, through decades of performance practice; and a few have even been previously published individually. Each individual song therefore is seen as constituting a ‘work’ for the purpose of this edition.

The total number of previously published songs located to date (2013) is 135. More than 50 extant unpublished songs are also published here for the first time and many more are known about but not yet traced, so the total number of songs may well rise to more than 200 by the time the edition is complete.

The songs are presented in two versions — staff notation only and staff plus tonic solfa notation — together with the original texts and English translations, and a piano reduction for rehearsal purposes rather than for accompaniment. The two versions of each song are justified by educational history: African choirs in southern Africa mostly do not read staff notation but only solfa, and it is hoped that seeing the output of a familiar composer in conjunction an unfamiliar notation might help overcome this problem and eventually help choirs to widen their repertoire. By the same token, these songs are hardly known outside Africa precisely because they were previously always presented in tonic solfa, so by giving a ‘staff-only’ version, people outside Africa can become better acquainted with this wonderful repertoire. (See African Choral Music: Editing African Choral Music and Mohapeloa Critical Edition: Editing Process.)

In Mohapeloa’s solfa scores, the original language matches the music word by word or syllable by syllable. Lines or phrases are often repeated, or left incomplete because of the polyphonic nature of the texture (one voice part may not have enough notes to complete the line). Different voice parts may have different texts. There are a number of melismas (syllables or words sung on more than one note). Nevertheless, it is possible to separate the song texts and present them as poems, as they are done here. The way Mohapeloa uses language, especially metaphor, is richly poetic. The texts usually describe a particular aspect of nature, landscape, and rural or urban life, or an emotion such as longing, happiness, anxiety. The last line often pulls a punch, adding a new twist to the meaning. Lines of text are discernible in the original songs because Mohapeloa begins each one with a capital letter. Occasionally, as in Meluluetsa (1976), texts were printed separately.

The translations are not there to be ‘sung to’ the notes but to help non-Sotho speakers understand what they are singing about. Texts are added for every voice part, and a brief commentary on each song is provided, to help with interpretation. The song texts alone constitute a major contribution to Sesotho literature, and the music offers a new perspective on composition in southern Africa.

It is hoped that this Complete Edition will be used not only by choirs, but also by scholars of music in southern Africa, for it allows, for the first time, a close study of a huge repertoire of music previously only known via a few isolated and often under-valued examples.

The author is dead and cannot be asked to approve the way music and texts have been presented in this Edition, but the musical score was an item of great importance to him, not only as a piece of music for performance but also as a record of African music’s history and development. He saw his own music as very much part of that development, rooted in the past while striving to satisfy the pressures of modernity.

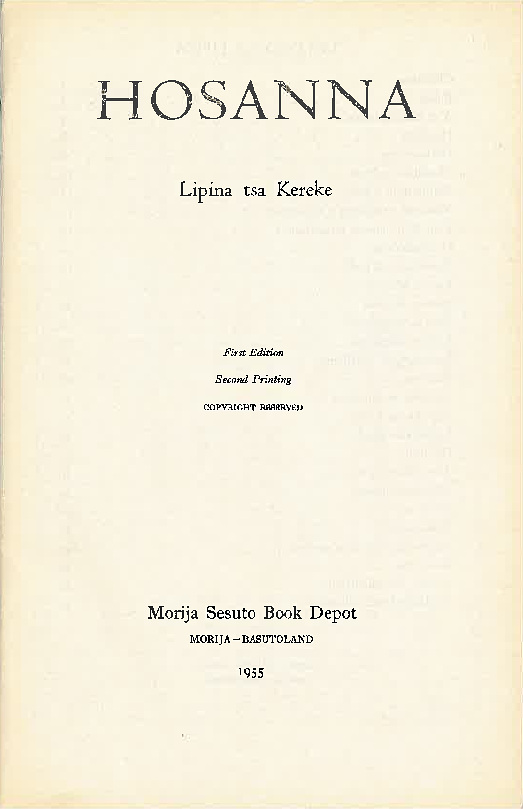

Publication was for Mohapeloa an essential part of the process of ensuring the continuity of African music, perhaps because he had seen so many examples of how oral tradition can die out. He wrote in the Khoro [‘preface’] to Meloli le Lithallere tsa Afrika book 1 (1935) that his scores were like cases (‘nyeoe’) presented to a court (‘lekhotla’). Such cases would ensure, he writes, that African Music would be ‘in the right place, where it is kept for the coming generations, as an example that they can follow, or a place to start when investigating about what proper African music should be’ (‘mehlala eo ba ka e salang morao kapa ba h hlakothisa phutsong ea seo ’mino oa Afrika e ka bang o nepahetse ha o ka ba sona’ — extract from Mohapeloa’s Khoro [‘preface’] to Meloli book 1, 1935).